In 1641 Massachusetts Bay Colony has the dubious distinction of being the first of Britain’s mainland colonies to make slavery legal. It was also one of the first State to abolish it 142 years later. The years leading up to and during the War were marked by a powerful moral contradiction: while townspeople rallied against British oppression, many continued to enslave African men, women, and children, or profited from systems dependent on slavery. This contradiction was not lost on many. Caesar Sarter, a formerly enslaved man, challenged the hypocrisy in 1774 in The Essex Journal and Merrimack Packet (a newspaper published in Newburyport), writing, “I need not point out the absurdity of your exertions for liberty, while you have slaves in your houses.” His statement exposed the moral gap between the ideals of the revolution and the lived reality of enslaved people in Massachusetts.

In Massachusetts slavery was present and persistent. It is estimated that the enslaved population before the War was 4,500 to 5,000 enslaved individuals in the 1760s–1770s, or 2–3% of the colony’s total population, predominantly residing in port towns. This pales in comparison to 40-60% of the Southern colonies’ total population.

Enslaved individuals lived and worked in homes and shops across Newburyport. The wealth of the town, too, was built partly on slavery—even among those who did not personally own slaves. Newburyport merchants were deeply involved in trade with the West Indies, exchanging fish and lumber (for barrel making) for molasses and sugar, grown and processed by enslaved labor on Caribbean plantations. This indirect collusion made labor exploitation a foundational component of the local economy.

Amid these contradictions, some voices within the colony spoke out. As early as 1716, Massachusetts Quakers questioned if it was morally right to enslave people. Prior to the war, these meetings (or assemblies) began disowning members who refused to emancipate the people they enslaved. Their principled stance was the first of an organized religious body in colonial America to demand abolition and helped pave the way for a broader moral reckoning, and later, deeply influenced William Lloyd Garrison of Newburyport.

During the Revolutionary War, the issue of slavery became even more fraught. In November 1775, General George Washington prohibited the enlistment of Black men—both free and enslaved—into the Continental Army. But as British officials began offering freedom to enslaved men who fled and joined their ranks, Washington reversed the policy. Soon, African Americans enlisted on both sides, often as a means to secure personal liberty. Purportedly 5,000 Black soldiers and sailors fought with Washington.

African-born Newburyport resident Pomp Jackson joined the army and became free. Prominent Newburyport merchant Jonathan Jackson emancipated Pomp Jackson on June 19, 1776, offering as his reasons “the impropriety I feel… in beholding any person in constant bondage—more especially at a time when my country is so warmly contending for the liberty every man ought to enjoy.” Pomp paid 5 shillings to Jackson for the privilege of being freed. Pomp Jackson had enlisted four days earlier in the Continental Army on 6/5/1776. He was at the infamous Valley Forge winter encampment and served as a fifer in the army for at least six years.

In his “History of Newbury” John J. Currier writes:

“Although the number of slaves in Newburyport was never very large the purchase and sale of negro men and women, brought from the Barbadoes and other islands in the West Indies, for some of the prominent inhabitants of the town, was not considered illegal or disreputable previous to the close of the Revolutionary war.”

In 1774, Deacon Benjamin Colman, of Newburyport, vigorously denounced ” the unnatural and unwarrantable custom of enslaving mankind ” …

The inspiring story of Caesar Hendrick has him winning his freedom through the courts and then enlisting in the Continental Army as a free man in 1780 to fight for the Americans.

“Caesar a mullato man, otherwise called Caesar Hendrick, laborer,” in March, 1773, brought a suit against Richard Greenleaf, Esq., of Newburyport, “for false imprisonment and restraint in servitude as the said Richard’s slave.”

This case was the first one involving the rights and duties of master and slave brought in the court of common pleas in Essex county, and the question in dispute was interesting and important. It was tried in Newburyport September 28, 1773…..

John Lowell, Esq., afterwards a justice of the United States circuit court for the district of Massachusetts, counsel for Caesar, obtained a verdict in his favor, and damages were awarded by the court, amounting to eighteen pounds.

In 1780, when the Massachusetts Constitution went into effect, slavery was legal in the Commonwealth. The tide had inexorably turned though. Successful lawsuits over the course of the next decade, and specifically three from 1781 to 1783, saw the Supreme Judicial Court apply the principle of judicial review to abolish slavery. Over this period, in Massachusetts at least, enslavers and enslaved people renegotiated their status. The 1787 Constitutional Convention debated slavery, but the framers believed that the concessions on slavery were the price for the support of southern delegates for a strong central government. By side-stepping, the framers sowed the seeds for future conflict 74 years later.

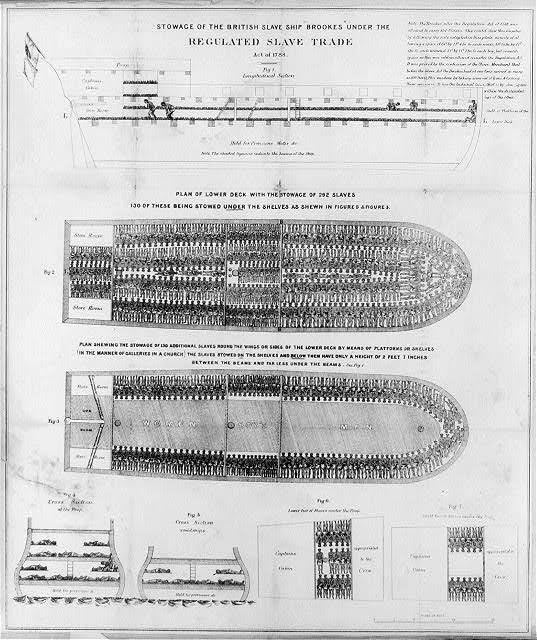

Stowage of the British slave ship Brookes under the Regulated Slave Trade Act of 1788

The campaign to abolish the Atlantic slave trade first emerged during the 1780s in Great Britain. Although slavery was not widespread in Britain, its merchants had long dominated the trade and helped to promote slavery throughout European colonies in the Americas and Caribbean. In 1787, abolitionist Thomas Clarkson joined with a group of English Quakers to launch a parliamentary investigation into the horrors of human trafficking. Clarkson conducted extensive research on the slave trade by touring British slave ports, interviewing crew, and collecting equipment from slave ships such as handcuffs, shackles, and branding irons. This famous diagram and description of the Liverpool-based slave ship, Brookes, shows the number and placement of Africans in the ship’s hold, contrary to the legal regulations of the slave trade. The layout, based on Clarkson’s information, was given as evidence during British Parliamentary hearings.

Special Thanks to:

Plan Your Visit

Plan Your Visit

- Museum Hours

Sunday: 12 pm - 5 pm

Closed Monday

- Tickets

$8 admission for adults

Free for NBPT residents, kids under 12, and museum members

Cost of admission includes access to the Discovery Center.

- Parking

City parking is available adjacent to the museum. View parking lot directions.