Written by Jack Santos

It’s 1779.

1779 is four years after 1000 soldiers on eleven ships left the docks of Newburyport in the early stages of the revolution, to conquer (unsuccessfully) Quebec City.

1779 is three years after the Declaration of independence – making an uprising a real declared war.

1779 is two years after Newburyporter Edward Wigglesworth, captain on a fleet of ships battling the British on Lake Champlain, valiantly maneuvered his ship to protect the retreat of the American fleet and save them to fight another day.

In 1779 Newburyport was still a hot bed of revolutionary sentiment, and recognized by the rest of the colonies, the newly minted UNITED STATES, as a leader and model of patriotism.

Local merchant Nathaniel Tracy was “all in” on the war. He had committed his fleet of trading ships to the task of privateering – harassing British ships, taking their goods, and sharing the spoils of war to support the cause.

Pirating, and its more legal cousin called privateering, could be very lucrative. Many became rich off the captured cargo and ships. But when face to face to the power of the British Navy off our shores, Nathaniel Tracy’s fleet was decimated over the course of the war. Tracy, whose home was the old section of today’s library, lost everything in support of the cause. He frequently conversed with George Washington, and even had him as a guest during the war (and after). He eventually had to sell his mansion to pay his debts and moved to a farm in the then outlying areas of Newburyport. Today that Farm is the Spencer Pierce Little farm owned by historic New England.

Tracy died young – age 45 – broken by war and economic trials. He gave everything to the cause.

But the story doesn’t stop there.

Recently a letter signed by Nathaniel Tracy came up for auction in California. It caught the attention of many local historians. The Newburyport Public Library archival center has another letter by Tracy – written at the end of his life while living on the farm in Newbury.

The auctioned letter was written at the height of his involvement in the revolution. It’s a letter to one of his privateer ship captains detailing instructions for a prisoner exchange in Halifax, a British port. In those days, under rules of engagement, captured officers were treated well. It was an interesting stratification of society – if you were enlisted, and not an officer, you could suffer the worst prison conditions imaginable. If you were an officer, both sides would treat you with the respect and dignity expected for that rank. A mutual understanding at the senior levels that reflected the inequality of war. Captured officers would frequently be invited to dinner with officers of the opposing side. They may even be released at their own recognizance, with a handshake understanding to not fight again – which would rarely be the case. War was a gentleman’s game.

The Library Archival Center letter written at the end of his life makes the case for tax abatement – not unlike requests city hall often receives today from senior citizens that can’t afford, or are behind on, their taxes.

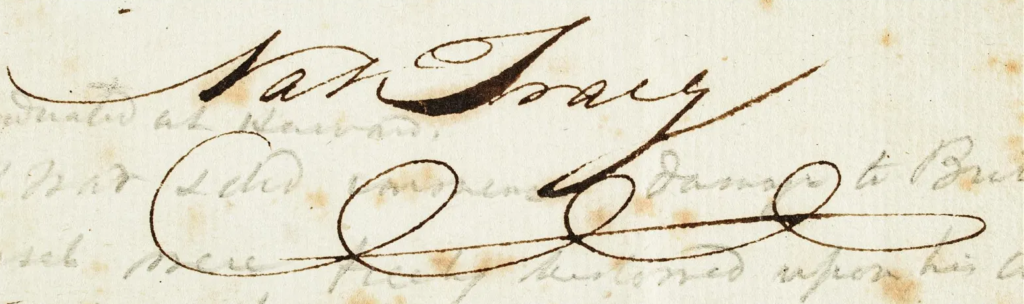

The letter the Custom House acquired is strong, directive, the kind of language spoken with confidence during a war. Tracy’s signature on the archival center letter is small, squeamish; I easily see it as the signature of a broken man that knows he doesn’t have much time left on this earth. Tracy’s signature on the war letter? Large, bold, with flourishes and broad strokes – this was a man at the height of his power, involved in a cause for the ages.

The Custom House Maritime Museum is proud to have been able to bid, and win, this letter for our collection – and bring it back home. We were able to do that through a generous donation by a local anonymous benefactor. We are working with archivists to stabilize the ink and paper, and will eventually put the letter on display, or make it available for research by appointment.

In the meantime, stop by the museum and learn more about Nathaniel Tracy in our “Legendary Newburyporters” exhibit – as well as all the other legendary Newburyporters- and celebrate the man that gave his all to our country’s fight for independence.