Until the 1840s, most Newburyport trade specialized in Europe and the West Indies, but as packet/medium clipper ships grew bigger, Newburyport merchants also began to sail for China, Burma, and India more regularly, and were gone for longer periods of time – voyages of two years became commonplace. Like the whaling wives of Nantucket and New Bedford, Newburyport’s merchant wives began to desire to travel with their husbands, and to make a home at sea.

Hannah Pettingell Jones

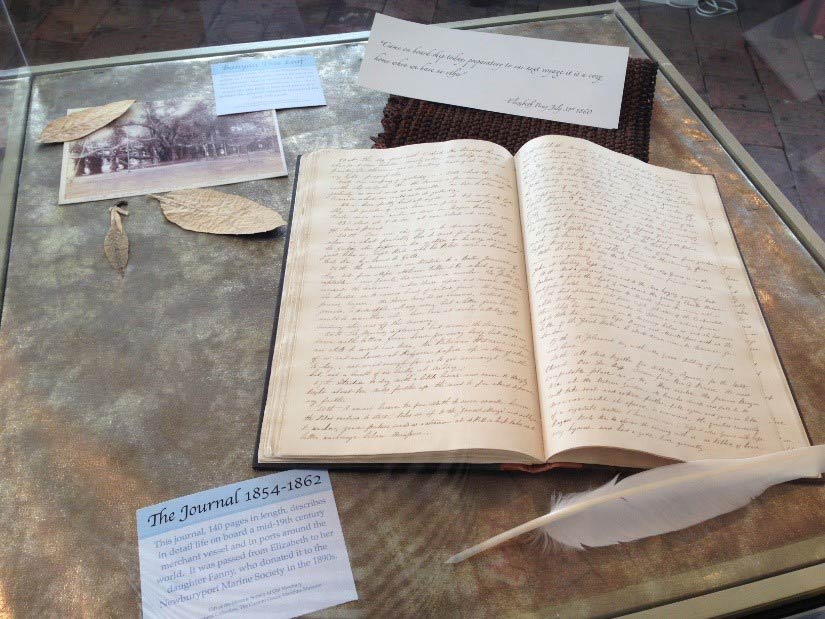

By tradition, Hannah Pettingell Jones is counted as the earliest Newburyport woman to travel extensively with her husband aboard ship. Granddaughter of merchant John Pettingell (1745 – 1823), one of Newburyport’s wealthiest men of the Federal era, Hannah married Captain Oliver O. Jones in 1836, and may have been accompanying her husband at sea at least as early as 1839.

In 1849, Hannah joined her husband and 14-year-old son, Oliver Jr., on board the ship James Caskie, for a six-month voyage around Cape Horn to San Francisco; this ship carried supplies for the Gold Rush and arrived in May 1850. At this early point, sea travel for captains’ wives could still be difficult, and socially isolating. Hannah would have been expected to stay below deck or in her cabin while her husband and son worked on deck, and she was not really free to associate with the crew. Hannah’s work would have included helping keep the accounts, and sometimes the logbook, in addition to more traditionally female duties such as sewing clothing and supplemental cooking.

Ports could prove equally dangerous and difficult for shipboard women. In Hannah’s case, while in San Francisco, with the crew all ashore, the Caskie was boarded by robbers. They attacked and nearly killed the captain in his cabin, forcing Hannah to surrender the ship’s cash. Captain Jones gradually recovered from his wounds – he even witnessed the execution of his attackers – but he died soon after returning home from a sea voyage in 1856.

Hannah remained a widow for the remaining fifty years of her life. Their son Oliver Jr., who was present during the attack on the Caskie, became a distinguished ship master in his own right, and spent much of the next forty years at sea.

Mary N. Lunt Graves

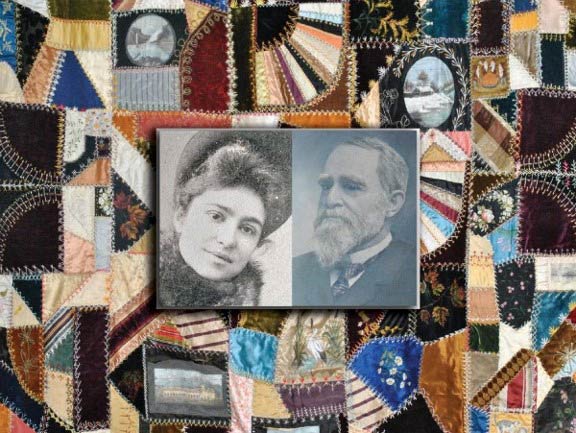

Mary Newton Lunt Graves also traveled at sea with both her husband and daughter, though for Mary Graves it was a more permanent arrangement. Mary married into the local Graves family of mariners in 1846. Mary’s husband, Alexander, and their daughter Mary Susannah, who went by Susie, traveled together aboard ships captained by Alexander, and owned by his older brother William Jr., for the next ten years. Before she was 13 years old, Susie had traveled 5 times around Cape Horn, and once around the world. Family tradition maintains that Mary Graves was the first Newburyport woman to circumnavigate the globe with her husband.

As Mary knew intimately, sailing was not without its dangers. In 1856, while commanding the ship Castilian off the coast of South America, Alexander was swept overboard by a heavy sea. A second wave washed him back aboard, but he broke his leg on the return. Mary helped take over the captain’s duties from her incapacitated husband and, under his instructions, aided in safely bringing the ship into New York Harbor. For that she received honorary captain’s papers and the gift of a lifetime membership in the American Seaman’s Friend Society from the ladies of Newburyport.

Alice Gray Brown

One of the last Newburyport women to go to sea aboard a sailing vessel was Alice Gray Brown. Traveling with her locally famous father, Lawrence, and her stepmother between 1878 and 1888, Alice went on six voyages, a couple of which were around the world.

By the last quarter of the 19th century, it was fairly commonplace to have women and families aboard ship. The Victorian family ideal applied even to families at sea, and the domestication of ships and ships’ crews transformed the utilitarian merchant vessel into a comfortable home on the ocean. One of the ships the Browns traveled on, the Mary L. Cushing, was even fitted out with red plush upholstery, and an upright piano in the cabin. Alice’s diaries sum up the differing experience of women at sea during the late Victorian age, when sailing ships were already something of an outdated anomaly, as steamships became the preferred transport for passengers. As noted by Alice in one of her diaries:

“I tell of lovely days spent on the Elcano, of which my Father was Master and my mother and I passengers. Ships passed and spoken, whales, sharks, flying fishes, porpoises, pilot fish, and others seen. Mostly fine weather spent. But also Rain, Heavy seas, calms. Shooting stars, wonderful sunsets and my Father reading many books aloud to us . . . We played cards – I painted. Had lessons. Did fancy work, plain sewing . . . Listened to Papa’s stories that I wish I could remember. Sundays always a sermon + service.”

Alice lived to be 93, dying in 1956. It’s hard to imagine the changes she witnessed over her long life – born in Newburyport during the Civil War, while her father’s ship was being burned halfway around the world in the South China Sea by a Confederate raider, travelling the globe in the last days of the great sailing ships, then witnessing air travel, World War II, and a television in the home.

Plan Your Visit

Plan Your Visit

- Museum Hours

Sunday: 12 pm - 5 pm

Closed Monday

- Tickets

Free for NBPT residents, kids under 12, and museum members

Cost of admission includes access to the Discovery Center.

- Parking

City parking is available adjacent to the museum. View parking lot directions.

250th Anniversary - American Revolutionary War Newburyport