The Brig Dalton and a Revolutionary War Prisoner’s Chronicle

The brig Dalton was a privateer vessel from Newburyport. Commissioned on October 7, 1776, she was armed with a formidable array of weaponry and manned by a crew of 120, under the command of Captain Eleazer Johnson. The Dalton embarked on missions to disrupt British shipping and support the American cause.

On December 24, 1776, the Dalton was captured by the British 64-gun ship HMS Raisonnable, a 64 gun third rate ship of the line, off Cape Finisterre, Portugal. The entire crew was taken prisoner and transported to Plymouth, England, where they were confined in Old Mill Prison.

Conditions in the prison were harsh, with prisoners enduring overcrowding, inadequate food, and disease. Some crew members, such as Charles Herbert, documented their experiences, providing valuable insights into the hardships faced by American prisoners of war.

Herbert was born in Newburyport. At just 19 years old, he joined the crew of the Dalton. In England, he suffered a bout of smallpox and was later accused of high treason. From 1777 to 1779, he was held at Old Mill Prison in Plymouth.

While imprisoned, Herbert secretly kept a journal documenting the daily life, conditions, and morale of the American prisoners. His entries reveal a life of hardship—hunger, illness, and punishment—but also of resilience and ingenuity. He described in detail the prisoners’ clever escape attempts, their camaraderie, and the discipline they enforced among themselves. Though most escapes failed, one notable tunnel in December 1779 allowed many to flee temporarily, including Herbert. He was soon recaptured and punished with half rations.

Herbert managed to support himself by crafting and selling wooden boxes, allowing him to purchase extra food and books. He often noted that his living conditions, while difficult, were better than most. His journal entries—some written in code—offer a rare, personal glimpse into the struggles of American prisoners of war and the spirit that sustained them.

In early 1779, Herbert was selected for a prisoner exchange arranged by Benjamin Franklin and was released in March. He later served under Commodore John Paul Jones aboard the Alliance and returned home in 1780.

In time, several other crew members were released through prisoner exchanges or escapes. Notably, Richard Lunt and Reuben Tucker, returned to service aboard the frigate South Carolina, continuing their fight for American independence.

Destruction of the American Fleet at Penobscot Bay by Dominic Serres. Raisonnable seen here in the far left background firing into Hunter on the Penobscot Expedition

The Penobscot Expedition: America’s Forgotten Naval Disaster

In July 1778, Raisonnable formed part of Lord Howe’s squadron, which was lying off Sandy Hook, NY. The French Admiral d’Estaing was nearby with a large fleet, and the two opposing sides were only prevented from engaging in battle by the weather and sea conditions, which forced the two fleets to disperse.

The largest American naval expedition of the war took place between July 24 and August 16, 1779. To spearhead the expedition, Massachusetts petitioned Congress for the use of three Continental Navy warships: the 12-gun sloop Providence, 14-gun brig Diligent, and 32-gun frigate Warren. The rest of more than 40 vessels were made up of ships of the Massachusetts State Navy and private vessels, many from Newburyport or with Newburyport crew members.

A fleet of 44 ships—19 warships and 25 support vessels—set sail from Boston on July 19, bound for the coast of Maine. Onboard were over 1,000 colonial marines and militiamen, including a 100-man artillery unit led by Lt. Colonel Paul Revere.

Their mission was to drive out British forces, including the Raisonnable, who had seized the strategic port of Castine and renamed the region “New Ireland.” Over three weeks, fierce fighting erupted across land and sea at the mouths of the Penobscot and Bagaduce Rivers.

The expedition was a disaster: scattered by the arrival of a British fleet on the bay, all of the expedition’s ships were captured, scuttled, burned, or abandoned, as noted by historian Joshua Coffin:

“An armament, consisting of twenty sail, besides twenty-four transports, appeared off Penobscot, destined to dislodge the enemy, but proved exceedingly disastrous. The Pallas, Sky Rocket, and so forth, sailed from Newburyport. Colonel Moses Little, of Newbury, was at first appointed to command the expedition, but declined, on account of ill health. August fifteenth, British recruits came to Penobscot. American forces ran up river and burned their own shipping.”

Captain William Nichols, Sr. noted that, after burning their own fleet to prevent capture by the British, he and his crew were then “forced to travel on foot through what was then an unbroken wilderness, to his home” – a 210-mile walk.

The destruction of the entire American fleet marks the worst naval defeat in U.S. history until Pearl Harbor in 1941.

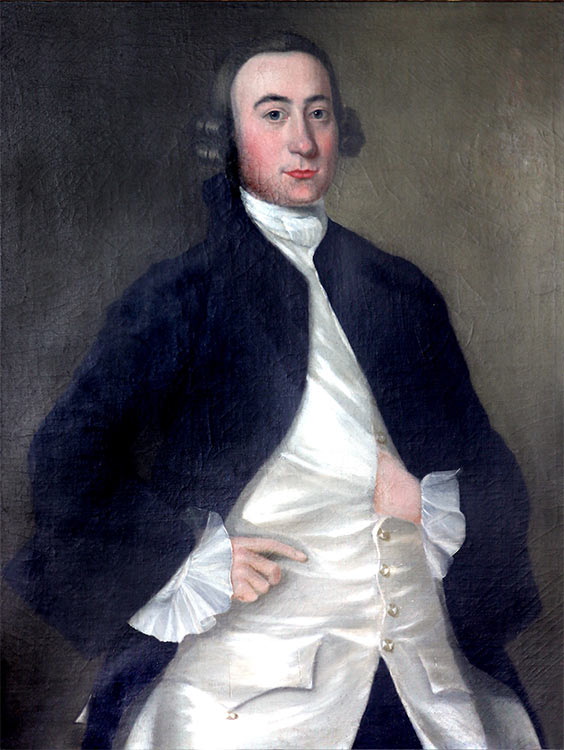

Who was Tristram Dalton?

Tristam Dalton (1738–1817) was a prominent Newburyport merchant and early American statesman. A Harvard graduate of 1755—alongside classmate John Adams—Dalton pursued commerce rather than law, inheriting a prosperous estate and business from his father, a former sea captain engaged in Atlantic trade. This inheritance made him one of Newburyport’s wealthiest citizens.

Dalton entered public life during the growing unrest preceding the American Revolution. In 1774, he was elected to the Massachusetts Provincial Congress and served on Newburyport’s board of selectmen. A strong supporter of independence, he lent his name to the Privateer Dalton and notably supplied ships for the Penobscot Expedition of 1780. He served in the Massachusetts House of Representatives (1782–1785), acting as Speaker in 1784, and later in the Massachusetts Senate (1786–1788).

In 1788, Dalton was elected as one of Massachusetts’ first United States Senators, serving from 1789 to 1791 during the formative years of the new federal government. He also advocated for the ratification of the U.S. Constitution and was a charter member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Dalton’s later years were marked by financial loss due to real estate investments in Washington, D.C.

Historical records indicate Dalton was one of two members of Congress from Massachusetts known to have enslaved a person. In 1804, he arranged for the burial of Fortune, a man he enslaved, in the consecrated Old Burying Hill Cemetery—an unusual and revealing act for the period.

Tristram Dalton died in 1817 and is buried at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Newburyport, His legacy endures in Newburyport, where the Dalton Club on State Street bears his name. The house was visited by a number of luminaries of early American history, including George Washington and the Marquis de Lafayette.

Special Thanks to:

Plan Your Visit

Plan Your Visit

- Museum Hours

Sunday: 12 pm - 5 pm

Closed Monday

- Tickets

$8 admission for adults

Free for NBPT residents, kids under 12, and museum members

Cost of admission includes access to the Discovery Center.

- Parking

City parking is available adjacent to the museum. View parking lot directions.