In 1774 Captain James Hudson, a member of the 2-year-old Marine Society, met with several of his fellow members at the Wolfe Tavern, then the hub of the town’s social and political life. By the time they left that night, the men had, in their patriotic fervor, formed a military company. This ‘Independent Marine Company’ is considered by some to be the “First Militia Company of Seamen mustered to defend American rights” – or the first Continental Navy company. The Company’s flag was “a blue anchor on a red field, supported by a pine tree and olive branch.” They also adopted a rule that “every neglect of duty by an officer should be subject to double the penalty imposed on a private.”

The Continental Navy, established by the Continental Congress on October 13, 1775, was an emergent force in America’s struggle for independence. Though modest in size compared to the formidable British Royal Navy, its creation marked a significant step in unifying the colonies under a national maritime force.

The primary objectives of the Continental Navy were to disrupt British shipping, protect American ports, and support military operations. Congress envisioned it as a means to wage a traditional guerre de course—a war against enemy commerce—aimed at weakening British supply lines and bolstering the American war effort. This strategy complemented the activities of Privateers, who, with congressional authorization, targeted British merchant vessels.

At its peak, the Continental Navy comprised approximately 60 vessels, many of which were small or lightly armed. Additionally, the Navy provided support for land campaigns and escorted supply ships, ensuring the movement of troops and materials essential for the Continental Army.

Despite its contributions, the Continental Navy faced significant challenges, including inadequate funding, a shortage of ships and manpower, and competition with Privateers for resources. These obstacles limited its effectiveness and led to the loss or capture of many vessels. Nevertheless, the Navy’s efforts laid the groundwork for the establishment of a permanent United States Navy, and its legacy endures as a testament to the resilience and determination of the fledgling nation.

The USS Hancock and USS Boston, both constructed in Newburyport, Massachusetts, were among the earliest frigates of the Continental Navy, and played important roles in the American Revolutionary War.

USS Hancock & USS Boston

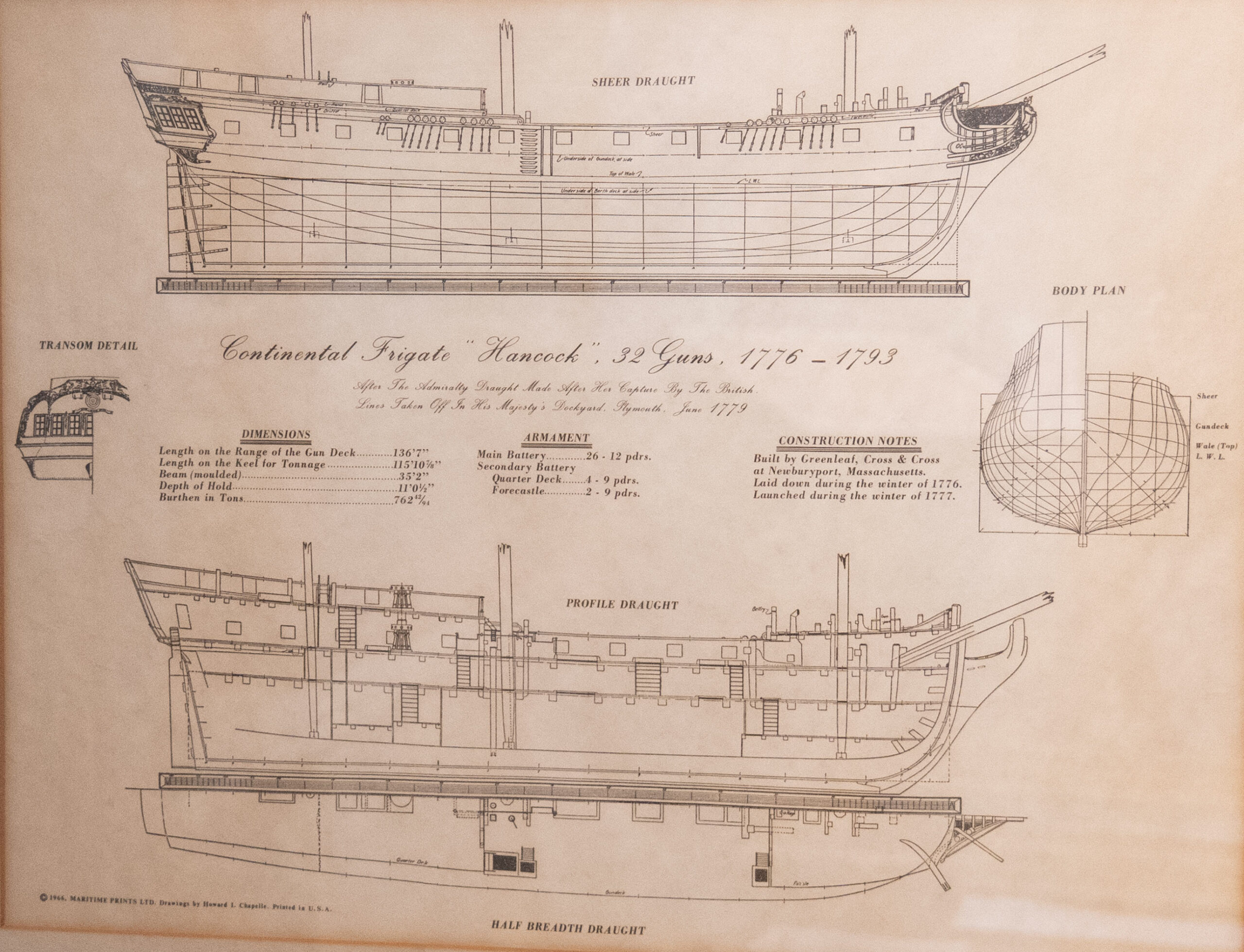

Authorized by the Continental Congress on December 13, 1775, the Hancock was among the first thirteen frigates commissioned for the Continental Navy. Built by Greenleaf and Cross in Newburyport. She launched under the command of Captain John Manley on April 17, 1776, the vessel faced initial delays in outfitting and crew recruitment.

The Boston launched on June 3, 1776 at the shipyard of Stephen and Ralph Cross in Newburyport. Smaller than the Hancock, she was a 24-gun frigate commissioned under Captain Hector McNeill. In May 1777, both vessels set sail from Boston along with the privateer American Tartar for a North Atlantic cruise.

On May 29, the Hancock and Boston captured a small brig laden with cordage and duck. The following day, they encountered a convoy escorted by the British 64-gun warship Somerset. Through strategic maneuvering by Captain Manley and his counterpart on the Boston, they evaded capture. Continuing their mission, the duo engaged the British 28-gun frigate Fox on June 7 compelling her to strike her colors (surrender).

However, the tides turned in July. On the 7th and 8th, the Hancock, Boston, and their prize Fox faced 3 British vessels off the coast of Nova Scotia. The Boston managed to escape, but the Hancock and Fox were captured after intense engagements. The Hancock was subsequently commissioned into the Royal Navy as HMS Iris, where she served with distinction. Impressed by her design, detailed measurements were made of her at the royal dockyard in Plymouth, England in 1779. Subsequent engagement led her to be captured by the French in 1781.

After her initial cruise with the Hancock, the Boston continued to serve valiantly. In early 1778, under Captain Samuel Tucker, she transported John Adams to France.

Virtually no measured drawings exist depicting early American vessels. Drawings were not part of the American shipbuilding tradition. This drawing is a reproduction of Howard I. Chappelle 1966 drawing.

Hancock Frigate

Tonnage: 762

Length: 140 feet; Beam: 30 feet; Depth: 10 feet

Armament: 32 12-pounder long guns

Complement: 290 officers, enlisted men, and Marines

Boston Frigate

Tonnage: 514

Length: 114 feet; Beam: 32 feet; Depth: 10 feet

Armament: 24 12-pounder long guns

Complement: 290 officers, enlisted men, and Marines

What is a Frigate?

During the Revolutionary War, the name frigate was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and maneuverability, intended to be used in scouting, escort and patrol roles. Typically a frigate had only one armed deck, with an unarmed deck below used for berthing the crew.

Special Thanks to:

Plan Your Visit

Plan Your Visit

- Museum Hours

Sunday: 12 pm - 5 pm

Closed Monday

- Tickets

$8 admission for adults

Free for NBPT residents, kids under 12, and museum members

Cost of admission includes access to the Discovery Center.

- Parking

City parking is available adjacent to the museum. View parking lot directions.