Debt from the Revolutionary War

When war broke out between Great Britain and its thirteen American colonies, the Continental Congress faced an urgent need for weapons, supplies—and money.

Lacking the authority to levy taxes, and with recent colonial opposition to British taxation fresh in memory, the Congress relied on the individual colonies to provide troops and financial support. But many of the colonies were unable—or unwilling—to contribute enough funds. As a result, Congress had to turn to borrowing.

In 1776, the Continental Congress issued $5 million in war bonds, offering 4% annual interest and a promise of future repayment. However, these bonds were backed not by gold or silver, but by paper currency. As inflation surged, colonial currency rapidly lost value—by 1778, it had depreciated by 80%. The bonds, once seen as a patriotic investment, lost appeal. Many bondholders sold them to speculators for a fraction of their original value.

In addition to domestic borrowing, Congress sought foreign aid. Benjamin Franklin, serving as a diplomat in Paris, helped secure financial support from France, Spain, and the Netherlands—nations eager to see Britain’s global power weakened. France alone provided an annual loan of 2 million livres with no set repayment deadline, though repayment was understood to be necessary in the future.

Meanwhile, many colonial governments also borrowed to fund militia efforts. Without sufficient funds to pay soldiers, they issued chits—promissory notes that functioned as IOUs. These chits did not accrue interest and were rarely backed by clear repayment plans.

After the war, managing this growing debt became a national priority. Alexander Hamilton, appointed as the first Secretary of the Treasury in 1789, introduced a financial plan to stabilize the young nation’s economy. Recognizing that tariffs on imported goods were one of the few viable sources of federal revenue, he emphasized the importance of custom houses like this one.

Hamilton also understood the economic harm caused by widespread smuggling. In response, he proposed the creation of a fleet of ten Revenue Cutters in 1790 to enforce tariff laws. The first cutter was launched here in Newburyport, giving the city the honor of being recognized as the birthplace of the United States Coast Guard.

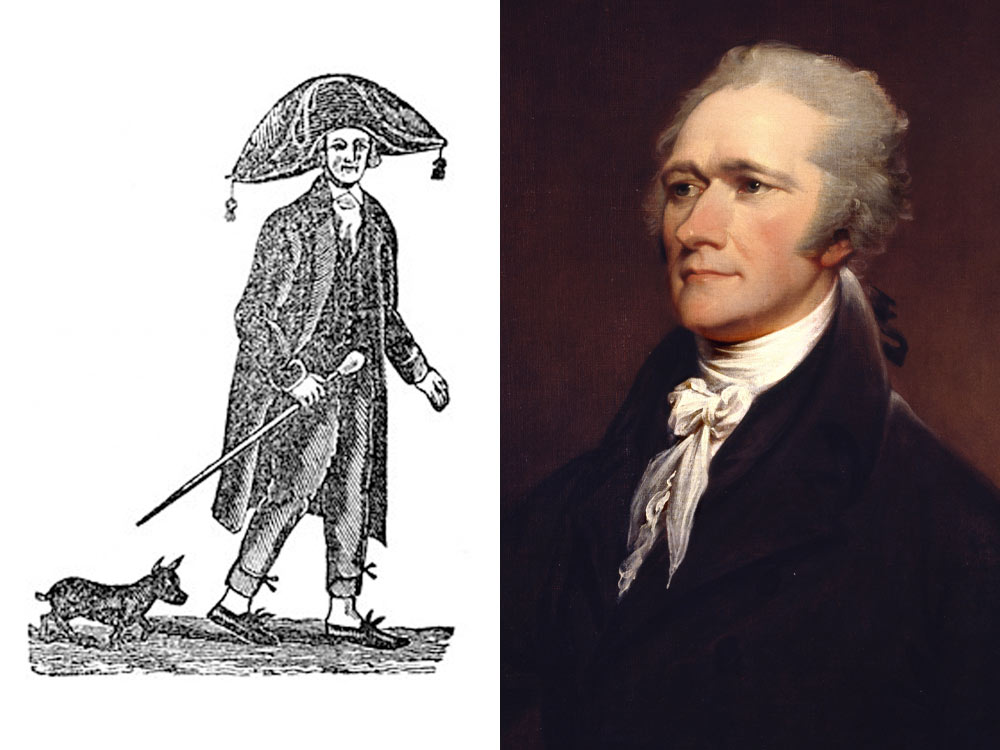

“Lord” Timothy Dexter (left) and Alexander Hamilton (right)

“Lord” Timothy Dexter (1747-1806)

Timothy Dexter was born in Malden, MA in 1747, a descendant of poor farmers. At the age of 21, he moved to Newburyport and, in 1770 married Elizabeth Frothingham, a wealthy widow. During the Revolutionary War, Dexter bought up a prodigious amount of Continental Dollars, purchasing these for a fraction of their face value. When the Federal government announced a new national banking system in 1791, offering face value for outstanding currency, the illiterate Dexter became of one of Newburyport’s wealthiest men overnight.

Special Thanks to:

Plan Your Visit

Plan Your Visit

- Museum Hours

Sunday: 12 pm - 5 pm

Closed Monday

- Tickets

$8 admission for adults

Free for NBPT residents, kids under 12, and museum members

Cost of admission includes access to the Discovery Center.

- Parking

City parking is available adjacent to the museum. View parking lot directions.