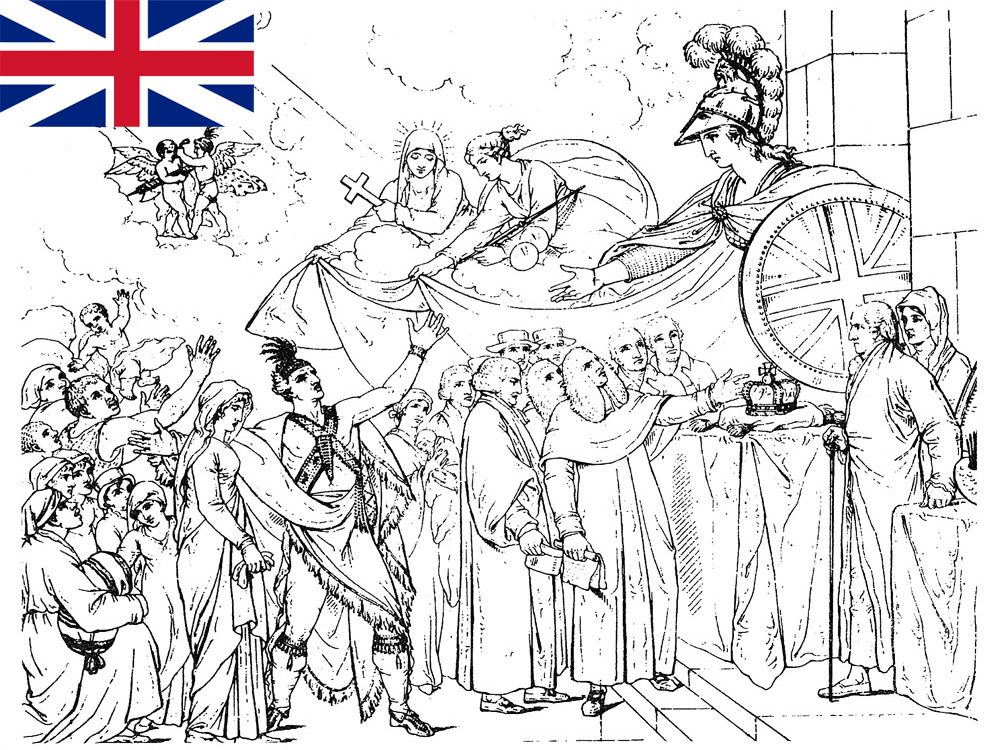

The American Revolution is often told through the lens of those who fought for independence. Less well known are the stories of Loyalists—colonists who remained faithful to the British Crown. Branded as traitors by many of their neighbors, Loyalists faced intimidation, property seizure, exile, and, in many cases, permanent displacement. Historians have called the conflict “America’s first civil war,” noting that between 60,000 and 100,000 people ultimately fled the colonies.

In Massachusetts, a center of revolutionary fervor, tensions between Patriots and Loyalists ran high. In towns and cities like Boston, Committees of Correspondence and Safety fueled suspicion and conflict. While some Loyalists fled, others stayed—some compelled to sign loyalty oaths, others remaining out of necessity or a hope for compromise. Their loyalty often reflected a range of motives: religious conviction, family ties to Britain, fear of instability, or allegiance to the principles of parliamentary governance.

Religion added another layer of division. Most Anglican clergy remained loyal to the Crown, while dissenting Protestant groups often supported independence. “We are now forbidden not only to speak but to think,” one Massachusetts Loyalist lamented, capturing the deep personal cost of the conflict.

In 1778, Massachusetts enacted the Banishment Act, formally exiling 308 individuals by name—many of them former colonial officials. That law marked a sharp turn toward punitive measures, and many Loyalists who had not already fled were forced to do so.

When British forces evacuated Boston in 1776, hundreds of Loyalists left with them, resettling in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, England, and other parts of the British Empire. Thousands of enslaved individuals who had joined the British in exchange for promised freedom also left. Some would later help found Sierra Leone in West Africa.

The end of the war brought little relief. The 1783 Treaty of Paris encouraged the states to restore property and rights to Loyalists, but Massachusetts resisted. Returnees were often met with hostility and suspicion. The 1778 Banishment Act, which allowed exile without trial, clashed with both the Massachusetts Constitution (1780) and the U.S. Constitution (ratified 1788), which prohibited such laws.

Seeking reconciliation and economic recovery, Massachusetts repealed its most restrictive measures in 1787, granting general amnesty. Influential leaders such as John Adams and Congressman Theodore Sedgwick supported the return of Loyalists, recognizing their potential contributions to the state’s growth.

Special Thanks to:

Plan Your Visit

Plan Your Visit

- Museum Hours

Sunday: 12 pm - 5 pm

Closed Monday

- Tickets

$8 admission for adults

Free for NBPT residents, kids under 12, and museum members

Cost of admission includes access to the Discovery Center.

- Parking

City parking is available adjacent to the museum. View parking lot directions.