The Seven Years’ War (1754–1763), the first truly global conflict.

The war involved all the major European powers including Great Britain and France. Though centered in Europe, the war spanned multiple continents, including North America. Military deaths worldwide are estimated at 820,000, not including civilian casualties due to raids, famine, displacement, and political upheaval.

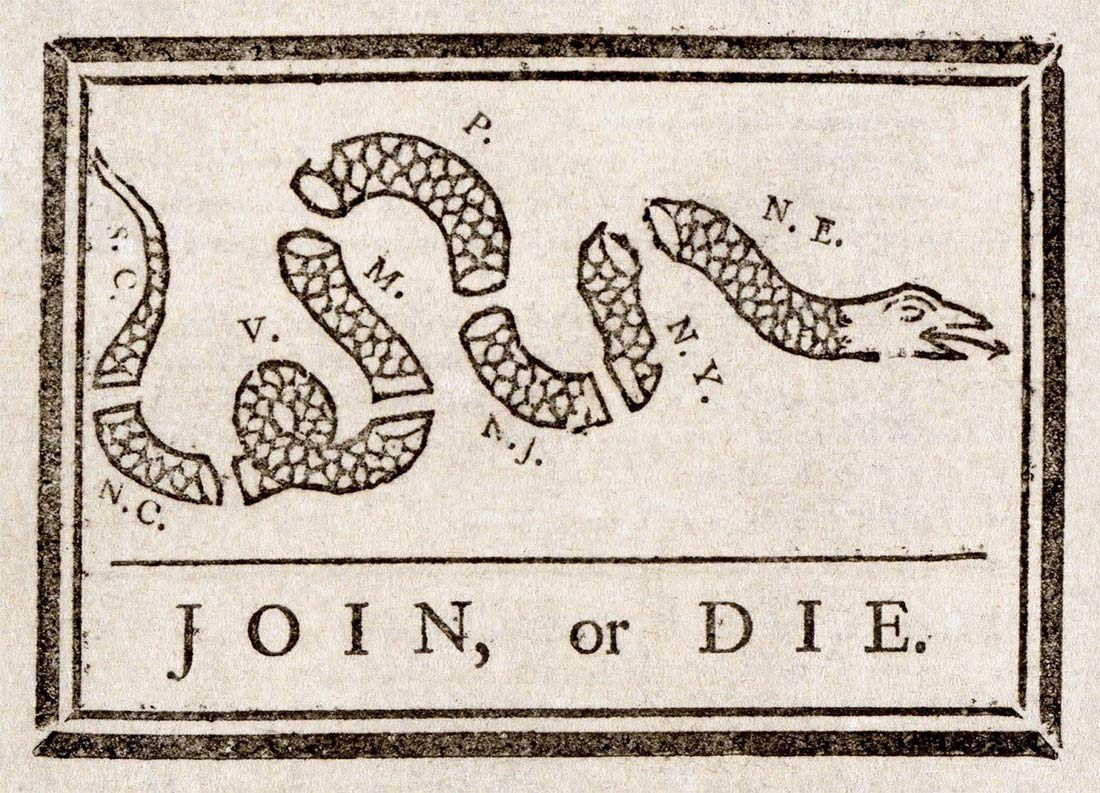

Published in 1754, Franklin’s cartoon urged the colonies to unite against the French and their Native American allies. The cut-up rattlesnake symbolized disunity among the colonies.

In North America, the war is known as the French and Indian War. Here, an estimated 25,000 deaths occurred among British and French troops, colonial militias, and their respective Native American allies.

The trigger of this global conflict was a territorial dispute between France and Britain in North America. Both nations held competing land claims. France sought to expand its influence forging alliances and trade relations with Native American nations. Rising tensions and repeated clashes over these contested lands ultimately led to open warfare.

The conflict began with a British defeat. In 1754, Virginia’s colonial governor sent a young officer, 21-year-old George Washington, to expel the French from forts in present-day western Pennsylvania. Washington’s forces suffered heavy losses and surrendered.

By 1759 British forces, with James Wolfe as 2nd in command, captured the Fortress of Louisbourg in Nova Scotia. Approximately 11,000 French Acadians were expelled, many perishing during their forced migration, with some resettling in Louisiana, where their descendants became known as Cajuns.

Wolfe, now promoted to General, set his eyes on Quebec, then under the command of the Marquis de Montcalm. The decisive moment came at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham. Newbury men were among those led by Wolfe. His death at the moment of victory became legend. Montreal surrendered to the British the following year.

The Treaty of Paris in 1763 ended the war. Britain emerged as the dominant colonial power in North America, gaining Canada from France and Florida from Spain. France effectively ceded all its territories, excluding New Orleans. It retained the valuable Caribbean islands of Guadeloupe and Martinique, prized for their lucrative sugar production.

Captain William Davenport led Essex troops under Wolfe at Quebec. In 1762, he opened an establishment under the sign of General Wolfe. Ironically, the tavern became a gathering place for Patriots. The Sons of Liberty rallied volunteers for the Continental Army and General Lafayette used the Wolfe Tavern as his headquarters. The original Wolfe Tavern was lost in the Great Fire of 1811.

Newburyport and the Seven Years’ War

William Bartlet – William Bartlet’s biography is similar to his contemporary and brother-in-law William Coombs. Born to cordwainer (shoemaker) Edmund Bartlet, William only attended school for a few years before apprenticing with his father. Also, like Coombs, and many other young men of his generation, Bartlet began to invest heavily in the local merchant trade that was booming during the 1760s. Bartlet married William Coombs’s sister Lydia in 1774, and records show joint ownership with Coombs of many privateers. After the war, Bartlet was able to purchase wharves, warehouses, and ships at a discount from merchants who had suffered financial difficulties during the Revolution. By 1807, Bartlet was the richest man in Newburyport having $500,000 – the 2nd richest man, Moses Brown, Esq., had holdings of only $272,000.

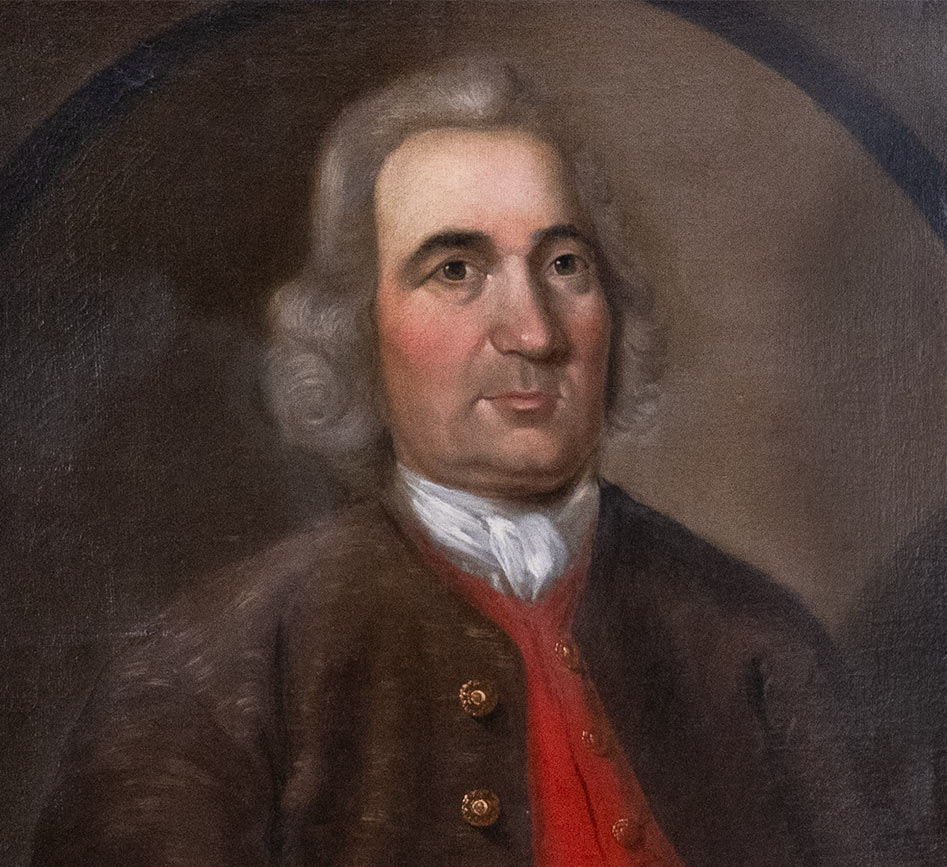

Philip Coombs – Born in Guernsey England, shipwright Philip immigrated to the colonies as a young man. By 1735, he had purchased riverfront property from fellow shipwright Ralph Cross to set up his own shipyard, and married Lydia Johnson. His son William was born the next year. Like most men of his era, Philip apprenticed his son in his business. In 1756, both Philip and William, along with Ralph and Stephen Cross, travelled with 18 Newbury ship builders to Lake Ontario to help construct vessels for transporting British forces and munitions during the French and Indian War. On August 15, the British surrendered Fort Oswego to the French, and Philip and William, along with 1,700 others, were taken to Dijon, France and confined in a stone fortress. Philip died there on January 2, 1757. His estate inventory notes a “River Lott 60 feet front with a Dwelling house & wharfe” which finally passed to son William in 1761.

Daniel Marquand – Like Coombs, Daniel Marquand was native of St. Martin, on the British Channel Isle of Guernsey, and was already a successful merchant when, in 1732, he relocated to the Newbury “Waterside,” and began to build up a new maritime trade business. In 1740, Daniel married Mary Brown and began a family; son Joseph, born in 1748, was the last of six children. In 1757, Daniel enrolled in a volunteer company and offered ships and stores to the Crown during their war with France. By 1776, now an old man, Daniel was an ardent patriot, even demanding of his church vicar that he “omit in your use of the Service all prayers which relate to [blessing or supporting] the King, Royal Family, or Gov’t of Great Britain.” By the time he died in 1789, Daniel had seen Newbury Port become its own town, witnessed a colony throw off the rule of the greatest military power on earth, and watched the new United States adopt a Constitution and elect its first president.

Patrick Tracy – Orphaned at an early age, Patrick’s guardian, according to family tradition, robbed him of his estate and in 1730, at 19, he sailed from Ireland to Boston. Settling in Newbury around 1737, Patrick became a mariner and learned navigation on several trips to the West Indies. This allowed him to become a master mariner and set up his own merchant business. On June 10th, 1763, Patrick was one of five signers of a petition to the General Court, on behalf of 200 Newbury “water side people” to incorporate their own town. It was granted the following year, and on February 8th, 1764, Patrick was made an officer of the new town – Newburyport. By 1774, Patrick was a justice of the peace, active in the local Committee of Safety, owner of many privateers, and an ardent supporter of the Revolution, as was most of his family.

Special Thanks to:

Plan Your Visit

Plan Your Visit

- Museum Hours

Sunday: 12 pm - 5 pm

Closed Monday

- Tickets

$8 admission for adults

Free for NBPT residents, kids under 12, and museum members

Cost of admission includes access to the Discovery Center.

- Parking

City parking is available adjacent to the museum. View parking lot directions.